Last Updated on February 11, 2026 by Christian Heide

The City Hall (Casa de la Ciutat) is the historic seat of Barcelona’s City Council. It is classified as a local cultural heritage site located in Plaça de Sant Jaume. As it is standing opposite the Palau de la Generalitat it is symbolizing the balance between municipal and regional power.

The building reflects centuries of architectural evolution, from its Gothic origins to later neoclassical and Renaissance additions. The Gothic façade (1399), originally served as the main entrance. With the city’s growth, a new neoclassical façade facing the square was added in 1847, giving the building its present dual character: Gothic solemnity and 19th-century symmetry.

In this blog post you will read about its history, architecture and its best kept secret.

Origins and the Consell de Cent

The history of the Casa de la Ciutat is closely tied to the Consell de Cent (Council of One Hundred), the governing body that administered Barcelona for nearly five centuries. In 1249, King James I of Aragon appointed four local magistrates granting the city limited self-governance. By 1257, he expanded this autonomy by appointing eight councillors empowered to select around one hundred advisors, formalized in 1265 as the Consell de Cent Jurats. The council’s structure evolved over time. By 1498, councillors were chosen through a lottery system known as insaculació – names were drawn from a sack, symbolizing impartiality. Local autonomy remained until 1716, when King Philip V’s Decree of Nueva Planta abolished Catalonia’s traditional institutions after the War of the Spanish Succession.

The Interior Courtyard

The interior courtyard, built in 1391, embodies the city’s Gothic civic architecture. It was once accessed through the Gothic façade but today is entered from Plaça de Sant Jaume. The design features Gothic arches resting on slender columns, an upper gallery with windows and balustrades, and a cornice with pinnacles and gargoyles. Renovations began around 1560, introducing Renaissance decorative details while maintaining the Gothic structure.

Though damaged in 1830, the courtyard was faithfully reconstructed in 1929 during the great restoration campaigns of the early 20th century. The right side of the courtyard houses the Galeria del Trentenari and the Staircase of Honor, leading to the Saló de Cent.

Over time, the courtyard has become an open-air sculpture gallery, displaying works by major Catalan artists such as:

- Saint George by Josep Llimona

- The Goddess (1910/1929) and Strength (1940) by Josep Clarà

- Mediterranean Spirit by Frederic Marès

- The Three Gypsy Boys and Maternity by Joan Rebull

- Woman by Joan Miró

- Seated Woman by Manolo Hugué

- Uranus by Pau Gargallo, among others.

The Gothic Gallery

Encircling the courtyard is a Gothic porticoed gallery, whose pointed arches stand on slender columns decorated with floral and angelic capitals. A dated inscription from 1577 marks one of its capitals.

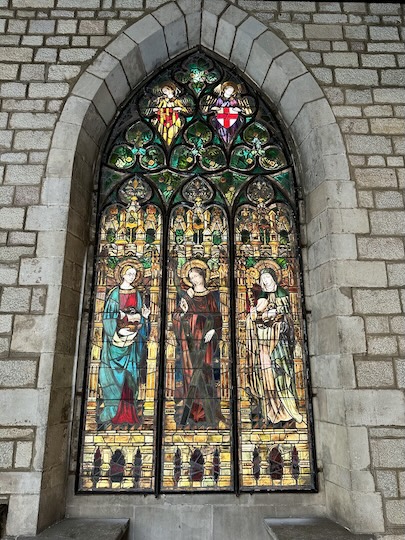

During the 1929 renovation the stained-glass windows installed were replaced with three new ones depicting:

- The city’s female patron saints: Madrona, Eulàlia, and Maria de Cervelló

- The male patrons: Saint Severus and Saint Oleguer

- The protectors: Saint Christopher and Saint Sebastian

This renovation sought to restore the gallery’s 16th-century authenticity. The vaulted ceilings were decorated by Josep Maria Sert, whose ocher-toned murals portray key figures in Catalan history and culture.

The Saló de Cent (Hall of One Hundred)

The Saló de Cent, the heart of Barcelona’s civic life, was built in 1369. This rectangular Gothic hall features a flat wooden ceiling supported by semicircular arches and illuminated by four rose windows. It hosted its first meeting on August 17, 1373, during the reign of King Peter III (the Ceremonious) – a date inscribed on a commemorative plaque within the hall.

In the 17th century, the hall underwent Baroque modifications, including a carved wooden choir and an altar screen. Later royal decrees in 1718, following the loss of Catalan autonomy, ordered the hall’s Gothic furnishings removed to match Spanish municipal standards, leading to its decline. By 1822, it had closed, and many Baroque works were sold. The bombardment of Barcelona in 1842 under General Espartero caused further destruction.

The Saló was restored in 1860, extending it with two new bays and reviving its civic function during Queen Isabella II’s visit and the revival of the Jocs Florals literary festival. In 1887, Domènech i Montaner proposed a new reform ahead of the 1888 Universal Exhibition, though his project was only partly realized.

The 1914 restoration by Enric Monserdà reinstated the hall’s Neo-Gothic character, adding a Gothic-style choir, a floor decorated with the city’s and trade guilds’ coats of arms, and an alabaster altarpiece (1924) depicting the city’s coat of arms guarded by mace-bearers. At its base stand Our Lady of Mercy, Saint Andrew, and Saint Eulàlia, flanked by medallions of Saint George and the Book of Privileges of Barcelona, and statues of Joan Fiveller and Rafael Casanova.

Sculptures of King James I and Saint George, created by Manel Fuxà, were placed under Gothic pinnacles restored in 1998 by Medina Ayllón. The entire hall underwent another careful restoration in 1996.

Conclusion

In the end, Casa de la Ciutat is more than just a seat of local government – it is a living reflection of Barcelona’s history and soul. When you slender through the building, it is like an art museum, each hall revealing layers of craftsmanship, symbolism, and civic pride. It is a true marvel that shows how beautifully the city’s past lives on in the present.

Yet its best-kept secret is wonderfully simple: on Sundays, entrance is free, giving locals and travelers the chance to explore this beautiful building without a ticket. It is the perfect opportunity to step inside, soak up the atmosphere, and discover a side of Barcelona many people walk past but few truly see.